At the time of this writing, the core archetypes of the new Mask of Light set are currently being worked out and getting their first few cards made. Usually, a good place to start doing this is at the start, or rather the starter – the first step in the combo that kicks off everything else. The design for this part is pretty straightforward, it’s simply a card that gets you to your other cards that do the stuff you’re trying to do. But what I’ve found recently is that things get a lot more fuzzy once you advance to the second step – the first card that you get to that then further enables the stuff you’re trying to do. Intuitively, this is something that extends your combo, so it’s easy to assume we can just apply the widely used term “extender” and be done, but as I’ll go on to elaborate, not every second step in a combo necessarily has the properties people tend to associate with extenders.

Let’s begin by defining more specifically what I mean when using these words. My understanding may differ slightly from that of any given reader or even the general community, especially as the use of terminology has evolved and continues to evolve with the game, so we won’t get anywhere without cleary setting out what things mean for the purpose of this writeup.

- The combo is the sequence of plays leading towards a certain game state a deck was built to achieve. Some decks have a single linear combo, some have many different paths leading to the same goal, others have multiple paths and goals, and again others just use their combo to accumulate resources and use them for a control style of gameplay. Any such sequence falls under the umbrella of “combo” here, not just the ones found in big spreadsheet decks. For the purpose of our examples, we’ll specifically consider a combo that leads to a field of two monsters A and B, potentially with some further advantage like B searching a Spell/Trap or whatever.

- A starter is a card which, if present in your opening hand, holds the potential to access the combo, with no prior setup required on your field, GY, or banishment. Starters that also work if nothing else is in your hand are 1-card starters, while those that need resources from the hand but aren’t picky are 1.x-card starters (where x is arbitrarily chosen based on how hard it is to satisfy the requirement). A card that only works as a starter if (n-1) other specific cards are present in your hand is a n-card starter, and I suppose it’s also valid for a starter to require setup on your opponent’s side (we could call this a conditional starter).

- An extender is a card that allows you to execute some portion of the combo, if and only if certain conditions are fulfilled in your field, GY, and/or banishment (in rare cases, other values like LP may be involved as well). Aside from being crucial to follow up your starter and actually make it into a combo, having an extender in your opening hand also allows you to extend and continue playing if your starter is stopped; this is the specific property I would argue is inherent to extenders, but not always to a “second step”.

- The second step in the combo is specifically the thing you do immediately after your starter resolves. What exactly it is depends on the form of the combo, in many cases it can also act as an extender, but its one and only defining property is, as the name suggests, the point at which it comes up in the combo.

Now for some different design approaches.

Design 1: The Taketomborg

The most classic extender-style second step, a monster that is added to the hand by the starter and can Special Summon itself from there if you control a monster from some category (e.g. archetype) that also includes the starter. So if everything resolves, you get to the goal of the combo with only the investment required by your starter, and if the starter is stopped, having the extender already in hand allows you to keep going and end up in the same place, just with 1 less extra card.

However, if you draw a card of this type as your initial piece of engine, you won’t be able to fulfill that condition to Special Summon it, making it either a brick or a Normal Summonable alternative starter – generally for a line not quite as good as the main starter’s, because otherwise that one wouldn’t be the main starter.

Finally, it’s worth noting there are a few seemingly exchangable, but actually quite distinct ways to write a “Special Summon self from hand” effect on card B.

a) If you control "A", you can Special Summon this card (from your hand).

Technically not an effect, but a procedure – doesn’t activate, can’t be hit by effect negates, but is vulnerable to the rarer Summon negates. At this particular point in time, the fact that this type of Special Summon plays around K9 can also be considered a significant advantage.

b) If you control "A": You can Special Summon this card from your hand.

Activates in the hand, thus can be chained to and negated. Arguably a strictly weaker version of the above, but also easier to adjust for synergy with more specific archetype gimmicks (for example, you can make it a Quick Effect). I’m also fond of this one because it can be covered by a regular HOPT clause along with the on-field effects, rather than needing its own “can only Special Summon … once per turn this way”.

c) If you control "A": You can Special Summon this card from your hand, then you can [...].

Not so much a variant as it is an extension of the (b) approach. This is an effect that activates in the hand, and then, while it resolves, performs an additional action rather than leaving that to a separate on-Summon trigger. Put simply, in the case where the action consists of searching something, this plays around Imperm at the cost of losing harder to Ash Blossom. Bit of an all eggs in one basket tradeoff.

Within the Bionicle YGOPro Expansion, somewhat straightforward examples of this design are Tamaru (who also works from the GY with a discard cost) and Midak (who sends an EARTH monster instead of directly Summoning himself).

Design 2: The Faris

Where the major weakness of Design 1 was its inability to leverage the free Special Summon in situations without the conditions provided by at least attempting to use a regular starter first, this next one aims to also cover those cases … for a price, that is.

The essence of this approach is a Special Summon that does not rely on particular preconditions, but just asks you to invest resources from your initial pool of cards and/or LP. The titular example I’ve chosen is Vision HERO Faris, who can be Special Summoned from the hand with an activated effect discarding another “HERO” as cost, and then advances your game plan once he has hit the field. As a classic second step, you can use this after Normal Summoning Stratos and searching it, but there’s also the option to Special Summon it as the first step if you open it directly.

A more modern example is Diabellstar, who instead gets brought out with a non-activated summoning procedure and has a far more generic cost, but functions much the same in principle – you can extend with it when you’re already playing, or start your plays by investing a resource less critical than the prized Normal Summon.

All of this, however, is contingent on being able to pay the cost. If you have zero cards in hand and your draw for turn is Faris, you can only Normal Summon it (and not even that is possible with the Level 7 Diabellstar). Worse, if your draw is Stratos, searching Faris won’t do anything, even though this would be full combo under Design 1. We also should not overlook that, in terms of card economy, having to pay even a small cost is going to add up in the long run; the tradeoff for greater starter/extender versatility is, in this case, being a bit less efficient at each of those things.

In BYE, a curious example of this design exists in the form of Taipu , whose Special Summon is seemingly free, but actually comes at the “cost” of restricting your attacks for that turn. Can be a surprisingly big problem outside of turn 1.

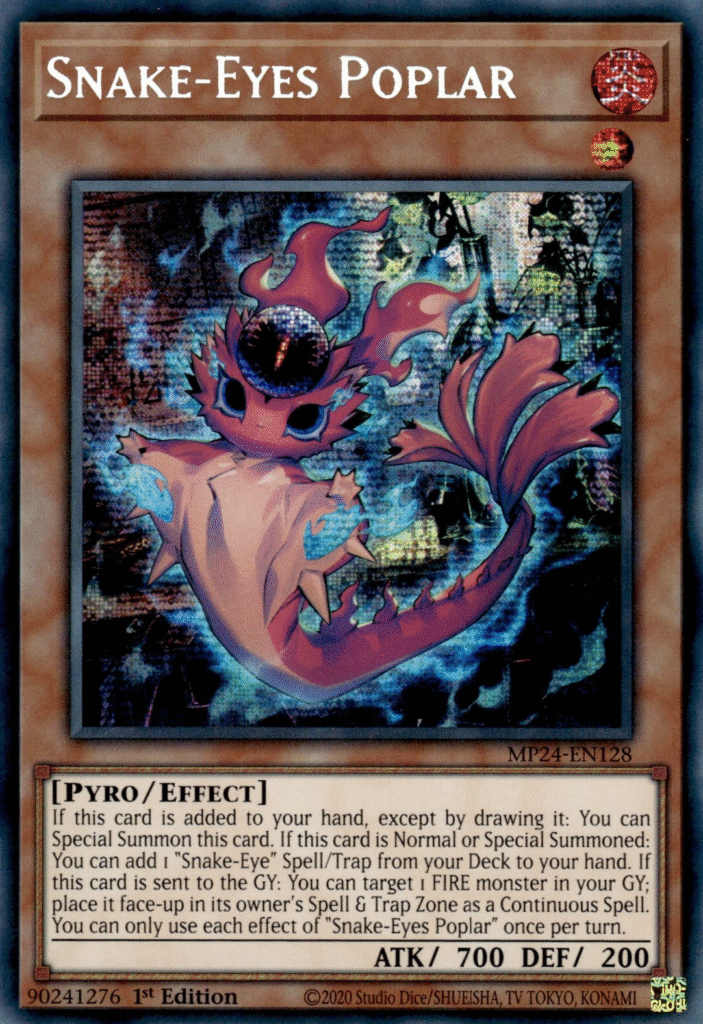

Design 3: The Poplar

Now for a category that has recently gained popularity: The second steps that, somehow, manage to not be extenders. They achieve this by having their effects that bring them to the field trigger specifically when added to your hand (by a card effect, or by any means except drawing, or even by any means except the normal draw), which is just what the first step of the combo does.

The namesake of this design is, of course, Snake-Eyes Poplar, which summons itself as the second step of the combo if added by the starter Snake-Eye Ash. What’s notable about the titular Poplar is that it’s a very powerful card even in isolation, capable of acting as a starter itself by searching Original Sinful Spoils and providing additional setup or recovery when it hits the GY. So I suspect that this particular design was chosen to conserve the power budget, so to speak, making sure you’re not able to access all these benefits for free unless you manage to resolve the preceding combo steps that search Poplar – having it in your hand already won’t help you if your Ash gets Ash’d.

Of course, technically having a card with this design can still increase the number of traditional extenders in your deck, because it grants that role to e.g. any Spell that’s able to search it. It’s certainly no coincidence Poplar and Bonfire were released only months apart.

And I guess it bears mentioning that, even though it has become the name everyone associates with this kind of effect, Poplar didn’t actually invent it. Machina Unclaspare had the exact same clause years before, and R-Genex Oracle did it (in a more archetype-locked fashion) all the way back in 2010.

In BYE … we haven’t used this yet, the design work so far mostly happened before this fad started. But it may just pop up somehwere sooner or later, since it is a pretty neat trick for giving something the second step role without directly increasing the number of extenders.

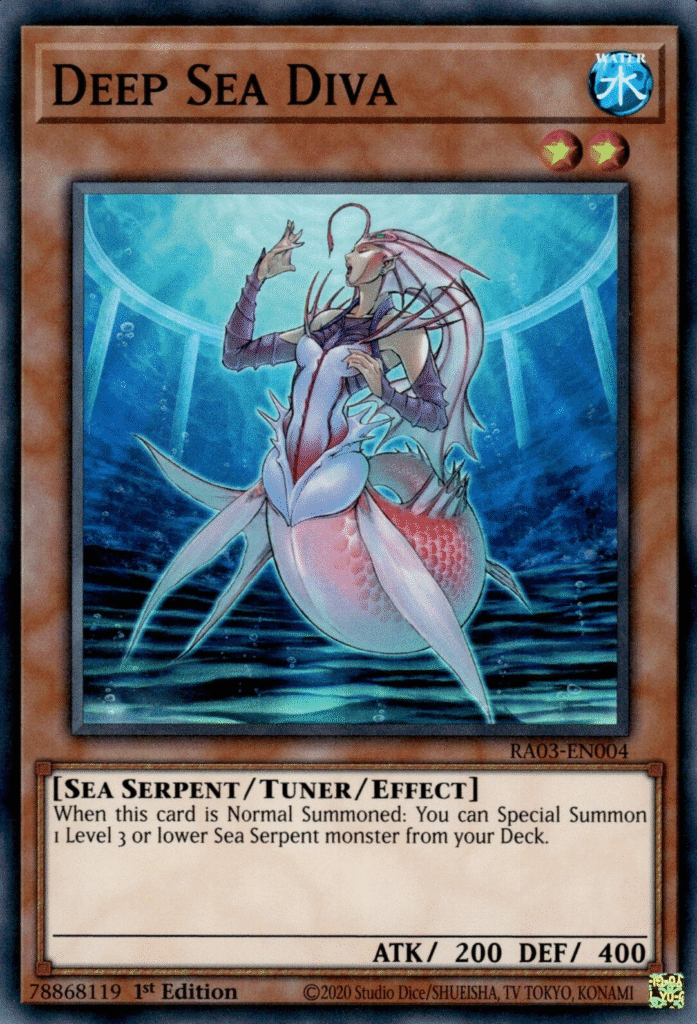

Design 4: The Deep Sea Diva

I know what you’re thinking. “Deep Sea Diva? That one’s not a second step! It’s just a starter!” Which, yes, but the end result of using the starter is suspiciously similar to the two-step combos where A searches B and then B comes down to the field. By having the starter Summon directly from the deck, the second step has been rolled into the first.

So what’s the advantage of doing it like this? Well, it lets you include a much wider range of cards into that basic setup of two monsters on the field, not just the ones that provide their own way to make the jump from hand to field. Diva enables this for all low-level Sea Serpents, and even less generic incarnations like the modern powerhouse Ice Ryzeal give access to their whole archetype without needing to use up any additional effects.

And the downside? Mainly that it spends power budget like crazy, hence why both Diva and Ice only do their thing if you invest the Normal Summon into them. It also concentrates a lot more power in a single card, making it a much more enticing and valuable target for any disruption your opponent may have. To top it off, if you’re using this kind of effect to bring out cards that otherwise cannot Special Summon themselves, that very trait means they won’t work as extenders if you do get disrupted – though Ryzeal has solved this issue quite handily by still giving everything in the archetype some ability to self-Summon, Ice just lets you skip that step so you can use it to extend later.

The example for this in BYE is Takua , who mixes in a bit of a fancy excavation gimmick, but ultimately works out to a guaranteed Special Summon of any Chronicler’s Company member from the Deck if you invest your Normal Summon.

Closing Thoughts

All in all, which design should we use? It depends™. If you want your card B to also work as an extender if card A is stopped, then the free conditional Special Summon fits best. But if card B is useful to bring out all by itself as well, it may be worth adding a cost so you can do that without requiring a condition or using the Normal Summon. Finally, designs 3 and 4 act as more specific adjustments to the power budget of the individual cards, the options they give you in deck building, and how effectively your opponent can interact with the combo. Hard to make a general statement on those, but it’s certainly worth keeping them in mind as options.